Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2018-11-22.

Avvicinandosi il Santo Natale tutti dovremmo essere più buoni, per cui useremo solo parole di miele.

I giudici della Corte Suprema tedesca sono liberal socialisti imprestati a quel Tribunale con il compito specifico di redigere a sentenza le veline loro passate dai rispettivi partiti politici. In questo nulla hanno da invidiare ai giudici in carica nel periodo dal 1933 al 1945, né alla Suprema Corte dell’Unione Sovietica dei tempi di Stalin.

Ma adesso i problemi iniziano a venire al pettine.

È un problema ingarbugliato, ma vedremo di semplificarlo così da renderlo comprendibile anche ai non addetti ai lavori.

*

Handelsblatt, il giornale della confindustria tedesca, affronta il tema dell’Alta Corte Federale di Karlsruhe senza peli sulla lingua, segno di quanto siano mutati i tempi. La voce di Frau Merkel è flebile e quella della spd inconsistente.

«Compared to how Germany’s constitutional judges are elected, the election of the pope is a paragon of transparency and democracy»

*

«As party politics seeps into decisions about who sits on the top courts of the US and Poland, Germany defends its reputation for judicial independence»

*

«But even here, the lines are more blurred that it might seem»

* * * * * * *

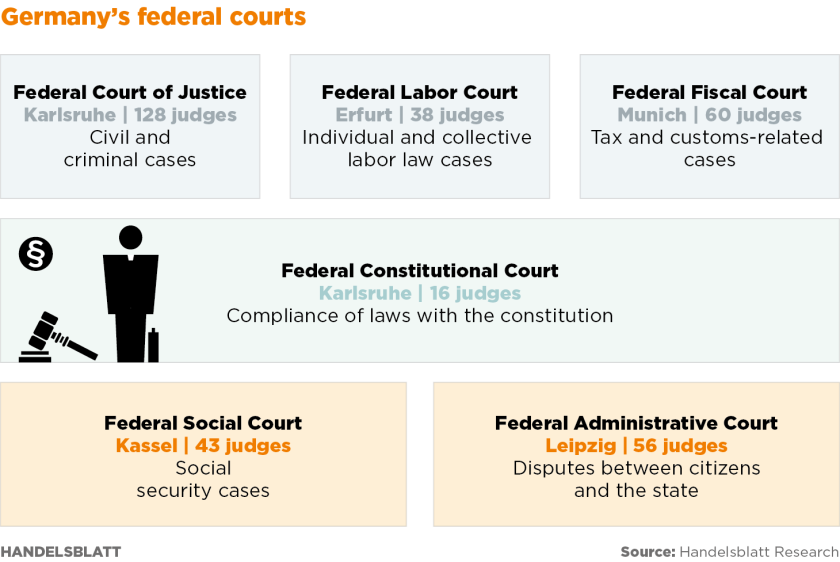

«Technically, Germany, unlike the US, doesn’t have one supreme court but six federal courts, each with a specific jurisdiction. The highest court handling civil and criminal cases is the Federal Court of Justice, or BGH. The Federal Constitutional Court’s role is to decide only whether laws comply with the constitution or not. This is a limited scope, but an extremely important one. Like the BGH, the top constitutional court is located in Karlsruhe, well away from the center of political power.»

*

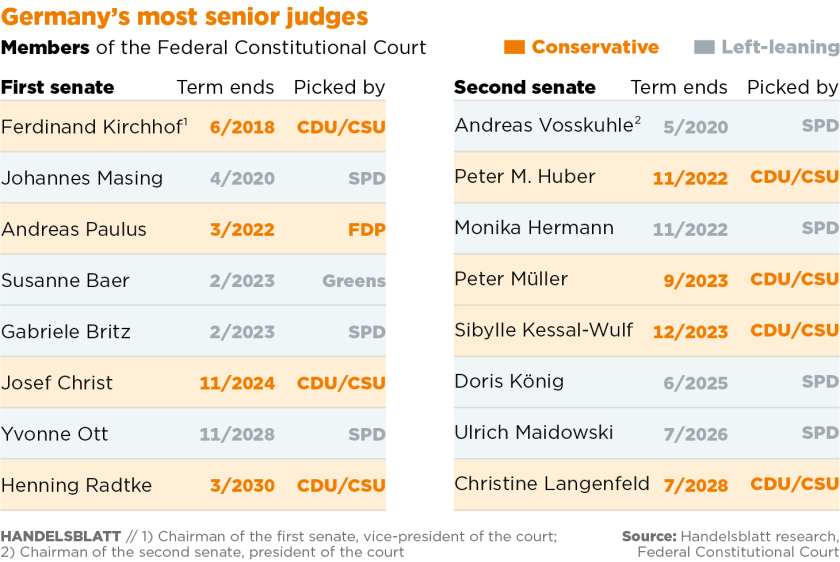

«Sixteen justices sit on Germany’s Federal Constitutional Court. They’re divided into two chambers — called senates — of eight justices each. An adequate candidate must be a federal judge of at least 40 years of age, among other criteria. While US Supreme Court justices have lifetime tenures, the 16 judges on Germany’s top court are appointed for a 12-year term. They cannot be reelected, “to ensure their independence,” the court’s website says. And they must retire upon reaching the age of 68»

*

«Germany is a shining example of a judiciary branch free from political interference is a stretch. In fact, politicians exert considerable influence on how the country’s top judges are appointed. Indeed, the Polish government never misses an opportunity to stress that Warsaw’s controversial judiciary reform is partly modeled on how Berlin selects its most senior judges.»

*

«“Poland wants to once again place its judiciary under democratic controls,” said Polish Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki earlier this year. “In Germany, for example, the justices of the highest courts are appointed by a committee for the election of judges,” he told the German press.»

*

«Germany’s nomination process to the Federal Constitutional Court is not only highly politicized but also opaque. A set of written and unwritten rules governs which party gets to pick a nominee; the selection process involves a great deal of political horse-trading, not to mention an ad hoc parliamentary committee whose work is shrouded in secrecy»

Saputo a quale giudice la causa è stata assegnata, la sentenza può essere scritta con mesi di anticipo. Divisione dei poteri? Ma se lo credano i gonzi!

*

«“Compared to how Germany’s constitutional judges are elected, the election of the pope is a paragon of transparency and democracy,”»

*

«Half the justices are chosen by the Bundestag — the lower chamber of parliament …. To be elected, a judge must obtain at least two-thirds of votes cast …. The other half of Germany’s constitutional court justices are chosen by the Bundesrat, the upper chamber consisting of the 16 federal states, also by a two-thirds majority»

*

«In practice, the supermajority requirement has enabled the two parties that have dominated political life for most of Germany’s postwar history — the CDU and the center-left Social Democrats — to evenly share the rights to pick a judge»

*

«The problem is that the mainstream parties need to reach a consensus on judiciary appointments to ensure a nominee gets a supermajority. This means that a lot of haggling takes place, most of it away from the public eye»

*

«The CDU/CSU bloc and the SPD have each selected seven of the 16 judges currently serving on the Federal Constitutional Court. The remaining two justices were picked by two smaller parties, the pro-business Free Democrats and the Green Party, because they have been in coalitions with the big-tent parties, either at the federal level or in state legislatures. They were only allowed to pick a nominee because the two bigger parties “let” them do so.»

*

«But as the combined dominance of the CDU and the SPD dwindles, the system is showing strain.»

*

«Thanks to the Green Party’s increasing strength in the Bundesrat in recent years, it recently obtained the right to hand-pick every fifth justice elected by the upper chamber.»

Un pensiero riguardo “Germania. Il mondezzaio della Corte Costituzionale. – Handelsblatt.”

I commenti sono chiusi.