Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2021-09-09.

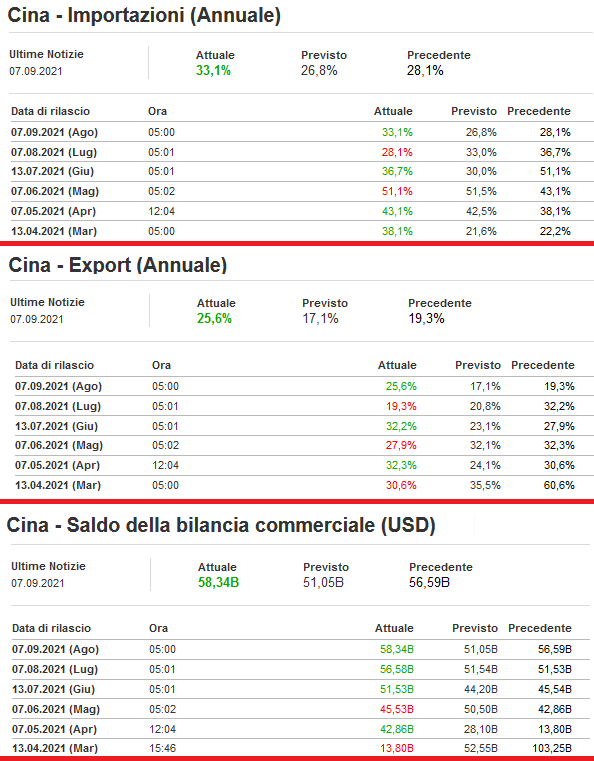

Così, il sistema economico cinese, dato dai media occidentali come agonizzante, ha segnato in agosto un Export del +25.6% ed un Import del +33.1%, confrontati con i valori rilevati nell’agosto 2020. Il saldo della bilancia commerciale è stato 58.3 miliardi Usd, per un valore annualizzato di 699.6 miliardi Usd.

I media occidentali sono esterrefatti, e si consolano dicendo che ” economic momentum has weakened”.

Ci si dimentica che per esportare occorre prima produrre, e che si importa ciò che poi dovrà essere lavorato.

Eppure, i rialzi dei costi delle materie prime ci sono anche per i cinesi.

* * * * * * *

«China’s August exports growth unexpectedly picks up speed in boost to economy»

«China staged an impressive recovery from a coronavirus-battered slump, but economic momentum has weakened recently due to Covid-19 outbreaks, high raw material prices and slowing exports»

«Shipments from the world’s biggest exporter in August rose at a faster-than-expected rate of 25.6% from a year earlier, from a 19.3.% gain in July»

«Exports from neighboring countries also showed encouraging growth last month, with South Korean shipments accelerating on strong overseas demand»

«Shipments from the world’s biggest exporter in August rose at a faster-than-expected rate of 25.6% from a year earlier, from a 19.3.% gain in July, pointing to some resilience in China’s industrial sector»

«→→ Analysts polled by Reuters had forecast growth of 17.1% ←←»

«August exports showed that despite a higher base for comparison from last year, the ongoing global recovery will not be impeded, and the impact from the resurgence in the Covid-19 pandemic remains limited»

«Export growth of machineries and hi-tech products stayed high»

«Exports from neighboring countries also showed encouraging growth last month, with South Korean shipments accelerating on strong overseas demand»

«China’s exports may sustain its strong growth into the fourth quarter, with overseas demand for Chinese goods over the Christmas season possibly exceeding expectations»

«the main constraint facing China’s exports right now is the very stretched international shipping capacity»

«A global semiconductor shortage has added to the strains on exporters»

«Imports increased 33.1% year-on-year in August»

«China’s trade surplus with the United States rose to $37.68 billion from $35.4 billion in July»

* * * * * * *

Nella foga verbale della guerra economica che gli Stati Uniti hanno intrapreso verso la Cina, accusandola di ogni possibile cosa che sia nefandezza ai loro occhi e sistematicamente sminuendone le capacità del sistema produttivo cinese, alla fine anche i liberal democratici sono obbligati a confrontarsi con numeri impietosi.

Europa. La stagflazione è in casa per rimanervi. Se ne pigli atto.

Europa. Luglio21. PPI, industrial producer prices, +12.2% su Luglio 2020. Inflazione a due cifre.

Usa. Nonfarm Payrolls 253,000. La débâcle economica di Joe Biden.

* * *

Una ultima considerazione.

Quale credibilità potrebbe ancora essere riposta negli ‘economisti’ occidentali che sbagliano in modo così vistoso le previsioni che fanno?

Si sono screditati con le loro stesse mani e con i loro fantasiosi giudizi surreali.

Gran brutto segno clinico il pensiero reso coatto dalla ideologia. Ha prognosi infausta.

*

China’s August exports growth unexpectedly picks up speed in boost to economy

– China staged an impressive recovery from a coronavirus-battered slump, but economic momentum has weakened recently due to Covid-19 outbreaks, high raw material prices and slowing exports.

– Shipments from the world’s biggest exporter in August rose at a faster-than-expected rate of 25.6% from a year earlier, from a 19.3.% gain in July.

– Exports from neighboring countries also showed encouraging growth last month, with South Korean shipments accelerating on strong overseas demand.

* * *

China’s exports unexpectedly grew at a faster pace in August thanks to solid global demand, helping take some of the pressure off the world’s second-biggest economy as it navigates its way through headwinds from several fronts.

China staged an impressive recovery from a coronavirus-battered slump, but economic momentum has weakened recently due to the delta variant-driven Covid-19 outbreaks, high raw material prices, slowing exports, tighter measures to tame hot property prices and a campaign to reduce carbon emissions.

Shipments from the world’s biggest exporter in August rose at a faster-than-expected rate of 25.6% from a year earlier, from a 19.3.% gain in July, pointing to some resilience in China’s industrial sector.

Analysts polled by Reuters had forecast growth of 17.1%.

“August exports showed that despite a higher base for comparison from last year, the ongoing global recovery will not be impeded, and the impact from the resurgence in the Covid-19 pandemic remains limited,” said Ji Chunhua, Senior Vice President of Research at Zhongtai International.

Export growth of machineries and hi-tech products stayed high in August, Ji said.

Exports from neighboring countries also showed encouraging growth last month, with South Korean shipments accelerating on strong overseas demand.

Some of the port gridlock also appears to have cleared in a boost to China’s shippers last month.

The eastern coastal ports have suffered congestion as a terminal at the country’s second biggest container port shut down for two weeks due to a Covid-19 case. That put further pressure on global supply chains already struggling with a shortage of container vessels and high raw material prices.

Zhang Yi, Beijing-based economist at Zhonghai Shengrong Capital Management, said China’s exports may sustain its strong growth into the fourth quarter, with overseas demand for Chinese goods over the Christmas season possibly exceeding expectations.

“We believe the main constraint facing China’s exports right now is the very stretched international shipping capacity.”

However, behind the robust headline figures, businesses are struggling on the ground. Companies faced increasing pressure in August as factory activity expanded at a slower pace while the services sector slumped into contraction. A global semiconductor shortage has added to the strains on exporters.

Imports increased 33.1% year-on-year in August, beating an expected 26.8% gain in the Reuters poll, buoyed by still high prices. That compared with 28.1% growth in the previous month.

China posted a trade surplus of $58.34 billion in August, versus the poll’s forecast for a $51.05 billion surplus and $56.58 billion in July.

Many analysts expect the central bank to deliver a further cut to the amount of cash banks must hold as reserves later this year to lift growth, on top of

July’s cut which released around 1 trillion yuan ($6.47 trillion) in long-term liquidity into the economy.

The country appears to have largely contained the latest coronavirus outbreaks of the more infectious delta variant, but it prompted measures including mass testing for millions of people as well as travel restrictions of varying degrees in August.

China’s trade surplus with the United States rose to $37.68 billion from $35.4 billion in July, Reuters calculations based on the customs data showed.