Giuseppe Sandro Mela.

2019-06-28.

«A panel of federal judges on Thursday ordered Michigan’s Republican-controlled legislature to redraw nearly three dozen state and U.S. congressional districts, ruling that the existing lines illegally dilute the power of Democratic voters»

*

Gerrymandering. Republicani e democratici si stanno scannando.

«If legislators fail to do so, or if the court finds the new district lines are similarly unconstitutional, the judges said they would draw the maps themselves. The redrawn districts would take effect in time for the 2020 elections»

«The state’s 14 seats in the U.S. House of Representatives are also up for election next year, and a majority of them could have new boundaries under the court’s ruling»

«The decision is likely a boon for Democrats, who in 2018 failed to win a majority of the seats in the state House of Representatives, state Senate or the state’s U.S. congressional delegation despite winning the overall popular vote in all three cases»

Il problema se le corti federali abbiano o meno il potere di interferire e, nel caso, surrogare e vicariare l’autorità politica legalmente costituita è approdato alla Corte Suprema, che il 27 giugno 2019 ha rilasciato la seguente sentenza.

«- The Supreme Court rules that federal courts may not block gerrymandering.

– The vote was 5-4 decision, falling along partisan lines.

– “We conclude that partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts,” wrote Chief Justice John Roberts, who delivered the opinion of the court.

– He says those asking the top court to block gerrymandered districts effectively sought “an unprecedented expansion of judicial power.”»

«Partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts»

*

Si faccia una grande attenzione. La sentenza vieta alle corti federali di non interferire con l’attività politica degli organi elettivi, non solo nel caso specifico, bensì erga omnes, perché costituirebbe una violazione della Costituzione ed “an unprecedented expansion of judicial power.”

*

Da quando gli Elettori hanno nominato Mr Trump presidente degli Stati Uniti, i liberal democratici hanno scatenato una guerra giudiziaria nella quale corti di basso livello, ma di chiara fede liberal, hanno sistematicamente bloccato le azioni politiche del Governo. Tutte codeste sentenze sono state poi cassate dalla Suprema Corte, ed anche malo modo, ma l’Amministrazione ne ha risentito, specialmente a livello internazionale, complice la cassa di risonanza dei media liberal.

Alla luce di codesta sentenza possiamo affermare che tali azioni furono il tentativo rivoluzionario di instaurare la dittatura dei giudici.

«an unprecedented expansion of judicial power»

I giudici devono solo attenersi alle leggi, astenendosi dalla politica.

* * * * * * *

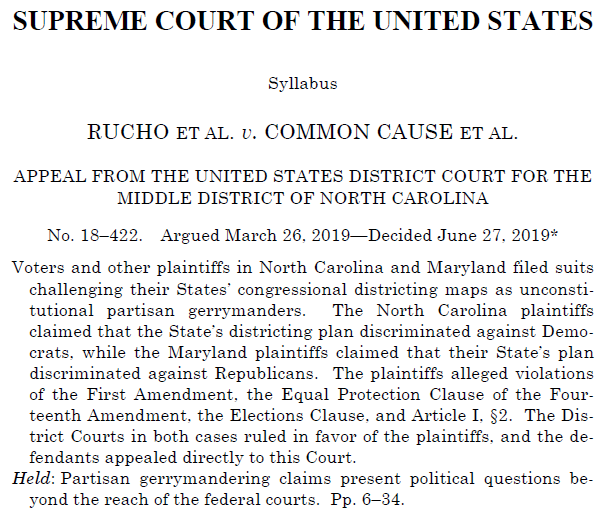

«Voters and other plaintiffs in North Carolina and Maryland filed suits challenging their States’ congressional districting maps as unconstitutional partisan gerrymanders. The North Carolina plaintiffs claimed that the State’s districting plan discriminated against Democrats, while the Maryland plaintiffs claimed that their State’s plan discriminated against Republicans. The plaintiffs alleged violations of the First Amendment, the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, the Elections Clause, and Article I, §2. The District Courts in both cases ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, and the defendants appealed directly to this Court.

Held: Partisan gerrymandering claims present political questions beyond the reach of the federal courts. Pp. 6–34.

….

In these cases, the Court is asked to decide an important question of constitutional law. Before it does so, the Court “must find that the question is presented in a ‘case’ or ‘controversy’ that is . . . ‘of a Judiciary Nature.’ ” DaimlerChrysler Corp. v. Cuno, 547 U. S. 332,

While it is “the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is,” Marbury v. Madison, 1 Cranch 137, 177, sometimes the law is that the Judiciary cannot entertain a claim because it presents a non justiciable “political question,” Baker v. Carr, 369

S. 186, 217. Among the political question cases this Court has identified are those that lack “judicially discoverable and manageable standards for resolving [them].” Ibid. This Court’s partisan gerrymandering cases have left unresolved the question whether such claims are claims of legal right, resolvable according to legal principles, or political questions that must find their resolution elsewhere. See Gill v. Whitford, 585 U. S ….

Courts have nonetheless been called upon to resolve a variety of questions surrounding districting. The claim of population inequality among districts in Baker v. Carr, for example, could be decided under basic equal protection principles. 369 U. S., at 226. Racial discrimination in districting also raises constitutional issues that can be addressed by the federal courts. See Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364 U. S. 339, 340. Partisan gerrymandering claims have proved far more difficult to adjudicate, in part because “a jurisdiction may engage in constitutional political gerrymandering.” Hunt v. Cromartie, 526

S. 541, 551. To hold that legislators cannot take their partisan interests into account when drawing district lines would essentially countermand the Framers’ decision to entrust districting to political entities. The “central problem” is “determining when political gerrymandering has gone too far.”….

Any standard for resolving partisan gerrymandering claims must be grounded in a “limited and precise rationale” and be “clear, manageable, and politically neutral.” ….

Partisan gerrymandering claims rest on an instinct that groups with a certain level of political support should enjoy a commensurate level of political power and influence. Such claims invariably sound in a desire for proportional representation, but the Constitution does not require proportional representation, and federal courts are neither equipped nor authorized to apportion political power as a matter of fairness. …..

The fact that the Court can adjudicate one-person, one-vote claims does not mean that partisan gerrymandering claims are justiciable. This Court’s one-person, one-vote cases recognize that each person is entitled to an equal say in the election of representatives. It hardly follows from that principle that a person is entitled to have his political party achieve representation commensurate to its share of statewide support.»

* * * * * * *

Sua Giustizia Roberts Allega Sua Su Opinione, tra cui leggiamo:

«The question is whether the courts below appropriately exercised judicial power when they found them unconstitutional as well.»